For generations, “Frankenstein” has been reshaped so many times that the version most people recognize barely resembles Mary Shelley’s original creation. The creature has marched through films, television, theater, parodies, and animation, but each reinvention has drifted farther from the haunting and thoughtful novel released in 1818. The result is a myth carried by lightning storms, green skin, and neck bolts—imagery that never existed on Shelley’s pages.

A closer look at the cultural trail of “Frankenstein” reveals how entertainment reshaped a story that was never meant to be a simple monster tale.

How Hollywood Rebuilt the Monster

Shelley’s novel makes a clear distinction: Frankenstein is the scientist, Victor Frankenstein, not the creature. Her protagonist is a young student immersed in “natural philosophy,” not a baron brooding in a gothic castle.

The creature he creates is far from the silent, lumbering figure familiar from film. Shelley’s version speaks at length, learns English on his own, and reflects on morality after encountering a copy of John Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” Entire chapters unfold from his perspective.

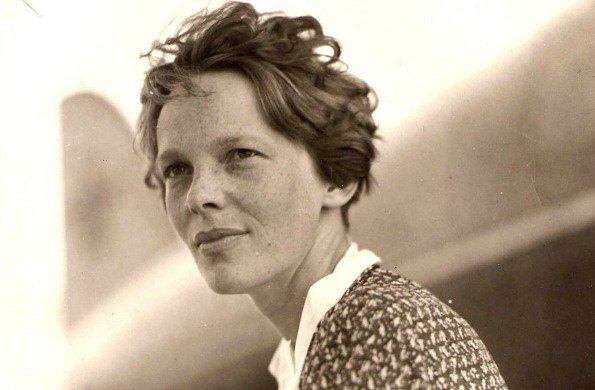

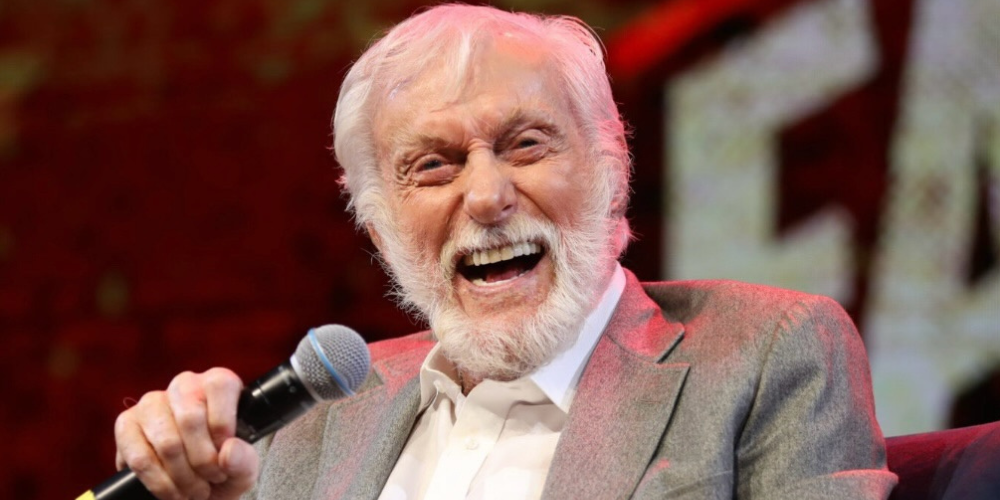

Instagram | theprytania | The canonical image of Frankenstein's monster was created by the James Whale’s “Frankenstein” (1931) film.

Yet the imagery most audiences accept as canon stems from two films that reset the cultural blueprint: James Whale’s “Frankenstein” (1931) and “Bride of Frankenstein” (1935). Boris Karloff’s performance, Elsa Lanchester’s iconic beehive hairstyle, the jolting lab equipment, and the now-standard “It’s alive!!!” were Hollywood inventions.

These elements became so recognizable that they overshadowed the creature Shelley designed—an articulate, observant being shaped by rejection, not stupidity.

The Monster’s Many Reinventions

The creature’s identity kept shifting as new filmmakers reinterpreted Shelley’s ideas. Hammer Films introduced a vivid run of adaptations beginning with “The Curse of Frankenstein” (1957) and ending with “Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell” (1974). These films often cast Baron Frankenstein, played by Peter Cushing, as a cold, obsessive figure, making him the true terror rather than his creation.

Alongside the horror versions came waves of satire, transforming the creature into a comedic icon. Titles such as “Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein” (1948), “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (1975), and “Young Frankenstein” (1974) treated the material with humor and theatrical flair. Television followed suit during the ’60s with “The Munsters,” where the creature became Herman Munster, a gentle suburban father.

By the time the “Hotel Transylvania” series arrived, the monster had softened into “Frank,” a friendly companion fit for family entertainment. The journey from Shelley’s tormented outcast to animated sidekick speaks volumes about how pop culture rearranges familiar stories to suit each era.

Films Capturing Shelley's Themes

Interestingly, several movies that never use the word “Frankenstein” align more closely with the novel’s intent than many direct adaptations.

Examples include:

“The Fly” (1986), which portrays the catastrophic fallout of scientific overreach when a researcher becomes his own experiment.

“Edward Scissorhands” (1990), where the focus shifts to the creature’s loneliness, innocence, and painful introduction to the human world.

“Poor Things” (2023), which reframes reanimation through a feminist lens as a resurrected woman claims autonomy, echoing themes rooted in the philosophy of Shelley’s mother, Mary Wollstonecraft.

These films share the novel’s concerns: unchecked ambition, abandonment, and the moral weight of creation.

Guillermo del Toro’s Faithful Adaptation

Instagram | joblomovienetwork | Del Toro's "Frankenstein," focuses on the Creature's empathy and Victor's paternal issues.

Guillermo del Toro’s recent interpretation of “Frankenstein,” starring Oscar Isaac and Jacob Elordi, steps closer to Shelley’s deeper themes. His adaptation foregrounds empathy for the creature and presents Victor Frankenstein as a man shaped by his own fractured relationship with his father. The creature, played by Elordi, carries innocence and vulnerability as he confronts a world unwilling to see him as anything but a threat.

Del Toro includes nods to earlier film traditions—like the lightning sequence and Isaac’s feverish bursts of madness—yet he directs the story back to its emotional center: the consequences of a creator who refuses responsibility. The film highlights the pain of a being born into rejection rather than horror born of violence.

Shelley’s questions remain strikingly current: What happens when creation races ahead of compassion? How does society treat beings it does not understand? With the rise of artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and technologies capable of reshaping life, the novel’s warnings feel less like gothic storytelling and more like a mirror held up to the present.

The Heart of Shelley’s Story

At its core, “Frankenstein” has always been a tale about creation and accountability rather than lightning bolts or stitched-together limbs.

Pop culture has transformed the creature countless times, but the enduring power of Shelley’s original lies in the emotional weight of abandonment and the danger of ambition without empathy.

Her story continues to survive reinvention because its questions still linger, challenging each generation to decide who the true monster really is.